- Home

- WHS McIntyre

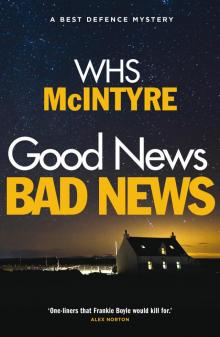

Good News, Bad News Page 2

Good News, Bad News Read online

Page 2

‘Quit moaning and keep walking,’ Joanna said. ‘It’s one dinner. I’ve not asked you to pull me out of a burning building.’ She stopped under the portico outside the Assembly Rooms, the crowd parting around us, rocks in a river of black suits and evening dresses.

‘Come here.’ Taking me by the shoulders, she squared me up and straightened my bow-tie with a couple of swift tugs. Joanna had binned the clip-on job that had served well for many a year and bought me a proper one that I’d had to learn how to tie. The dinner suit was also new. According to Joanna, borrowing my brother’s tuxedo and Wonder-Webbing the hems of the trouser legs was no longer an option.

‘Right,’ she said, giving me a helpful shove in the back, ‘shut up, get in there and smile.’

The Scotia Law Awards Dinner was an annual event, which in previous years I’d had little difficulty avoiding. For one thing I’d never been in the running, for another the tickets were one hundred and fifty a head.

‘So, how do you win one of these awards?’ I asked. ‘I don’t remember ever being asked to vote for anyone. Do you?’

‘Seriously?’ Joanna said, divesting herself of her coat and handing it to me. ‘You really think there are lawyers out there who would vote for other lawyers to receive an award?’ My wife-to-be was definitely in the running for most cynical lawyer of the year, and, it seemed, if there was a prize for the most gullible I’d be sole nominee. ‘I think that’s why I love you, Robbie. You always try and see the best in everyone.’

I did. Well, almost everyone. Obviously, exceptions had to be made in the case of certain politicians, most sheriffs and all but the very latest recruit to the Procurator Fiscal Service.

‘The way these things work is that Firms vote for themselves. They apply, saying why they should receive the award, and the organisers consider the written submissions very carefully along with the number of tables each firm is taking at the dinner. Book enough tables at fifteen hundred a go and they might even tailor an award especially for you.’

‘Most dashingly handsome. Something like that, you mean?’

Joanna took my chin in her hand and kissed me. ‘Yes, if it was me who handed out the awards.’

‘And if it wasn’t?’

‘I don’t think they have that many tables.’

I checked in our coats and brolly and once more we entered the stream of diners coursing towards the ballroom. The place was buzzing. Crystal ware and silver cutlery twinkled and glinted on fifty or so large round tables. Everywhere people mingled, laughed, sipped fizzy wine and generally looked very much like what they were: a bunch of lawyers who needed to get out of the office more often. I was cornering a tray of canapés that had foolishly strayed into range, when Joanna took my hand and dragged me towards an arm that was waving in the distance.

The arm, like the rest of the tall, lean body to which it was attached, belonged to Joanna’s Uncle Ted. Ted Hawke was Joanna’s mother’s brother and a partner in Fraser Forrest & Hawke. I’d only met him once, fleetingly.

‘Ted’s an insolvency specialist,’ Joanna said. ‘If you get stuck for conversation you can always talk about the law.’

That was all very well, but what did insolvency practitioners actually do? Years ago I’d lost track of what those other lawyers, the ones who didn’t stand up in court and argue for a living, did to make ends meet.

‘He oversees the restructuring and trading of distressed debt.’ Was there any other kind of debt? ‘Just don’t get involved in courtroom chat. The people at our table will be proper lawyers.’ By which Joanna meant not the type of lawyers who spent their days shouting at hostile witnesses and arguing the toss with uninterested sheriffs. Or maybe it was the other way around.

‘Ah, the guests of honour have arrived.’ Ted gave his niece a peck on the cheek and me a hearty slap on the back. ‘Good of you to join us last minute.’ Clearly, the years spent dealing with all that distressed debt hadn’t rubbed off on Uncle T financially. His fifty-something frame was covered with an evening suit that unlike mine hadn’t been pulled off a peg, and beneath it was a shirt so startlingly white it was sore on the eyes.

‘No, thank you for asking us,’ Joanna said, multi-tasking with a gentle dig in my ribs.

‘Yes, very kind of you, Ted,’ I said.

Our expressions of gratitude were dismissed with a friendly wave of his hand. ‘It’s nothing. We always take four tables at the Scotias. It’s something of a standing order, and this year we had a few last-minute call-offs. I’m only glad you could make it on such short notice. We’re up for a few gongs, and it doesn’t look good if our tables are half empty.’ He pulled out a chair for Joanna, and the other dinner suits at the table, recognising the relationship between the boss and my fiancée, rose while she took her seat.

Leaning over us, Ted rested a hand on Joanna’s and my shoulders. ‘Now that we have two of our criminal law contingent here, let me introduce you to the person I hope will be the star of tonight’s show.’ He gestured to a sturdy young woman sitting directly across from us. ‘Joanna, Robbie, this is Antonia. She’s the daughter of a very good friend of mine and the best legal trainee we’ve ever employed at F, F and H. Present company excepted, of course.’ He smiled at the other faces around the table, some of which looked like they were sucking the lime from their gin and tonics.

Antonia stood, reached across and shook our hands. She had a cute little smile, but you wouldn’t have wanted to arm-wrestle her for a pint.

‘And that’s why,’ Ted continued, ‘Antonia has been nominated for Legal Trainee of the Year.’

‘Well done,’ Joanna said. This from the woman who five minutes ago had told me what a fake the whole award ceremony was.

The young woman treated Joanna to her lovely smile. ‘We’ve met before, you and I,’ she said. ‘It was two years ago when I was doing the Diploma and you came to Edinburgh Uni for a mock trial. You were the Procurator Fiscal, I was the complainer. My imaginary shop had been robbed.’

Joanna’s half-open mouth, wide eyes and slow-motion nod of recognition told me she had no idea who the girl was. ‘Of course. Remind me. How did I do?’

‘You won. Guilty as libelled,’ Antonia said. ‘I think it was my identification evidence that swung it.’

I didn’t know why, but there was something in the way she said ‘guilty’. It made me feel not so much that someone was walking across my grave, more like they were bouncing all over it on a pogo stick.

Ted shook his head. ‘Crime, eh? All the young lawyers want to do it. All the smart ones know it doesn’t pay. No offence, Robbie.’ He laughed and threw an arm over my shoulder. I’d liked Ted from the word go. ‘Let me buy you a drink.’ I was a good judge of character. ‘I hear tell you’re fond of the uisge beatha.’

‘I’d rather have a whisky if you don’t mind,’ I said. Ted looked at me for a moment. It was a look that said, “This guy is a criminal lawyer. Not only that, he’s a Legal Aid lawyer. Yes, he really could be that stupid.”

I smiled to show I was kidding and he smiled too. With a wave of his magic arm, there was a waiter at our table in an instant, and a round of drinks swiftly followed.

As I sipped at what I hoped would be the first of many single malts, I began to think that perhaps it might not turn out to be such a bad evening after all. That was until I heard a horribly familiar voice behind me, and the exclamation, ‘Granddad!’

Antonia stood and skipped around the table towards us.

‘Am I the last?’ said a voice.

It couldn’t be.

‘I’m afraid I was guilty of thinking it would be easy to find a taxi on a wet Thursday night in Edinburgh.’

It was. There was no mistaking the ‘guilty’ in that sentence. Not when I heard the word on so frequent a basis. I turned slowly in my seat. The late arrival was clad in tartan trews, an Argyll jacket secured midriff by a single square silver button. He had more hair than I thought, but then it was always covered when I saw him.

&

nbsp; Sheriff Albert Brechin gave Joanna a stiff little nod of the head. ‘Miss Jordan, how nice to see you. I hadn’t realised you and Mr Munro would be coming tonight.’ He snapped me off a brittle smile that I was unable to return.

‘Likewise,’ I said.

4

Antonia Brechin was called to the stage to be crowned Legal Trainee of the Year, shortly after Uncle Ted had narrowly missed out on the Managing Partner award, and before a group from another city Firm was given the accolade of Public Law Sector Team of the Year, an area of law with which I was unfamiliar, and probably as boring as the title suggested. The whole presentation ceremony seemed to go on forever, with speeches, photographs and a big screen Twitter feed for lawyers to send gloating messages to other lawyers who hadn’t voted for themselves or bought enough tables.

I tried to drink my way through the boredom, but even half a bottle of wine and a few single malt digestifs couldn’t exorcise the ghost at the feast. Now I knew why Brechin had come back early from his holiday in Madeira. Not only to convict my boyfriend-slapping client, but also to share in his granddaughter’s moment of glory. How could it be that he acted so normally in company, almost like a human? Everyone else seemed to find the old git thoroughly charming.

Ted, for one, was finding the Sheriff’s conversation particularly stimulating. Was it only me who could sense his malevolent spirit?

‘You know what I’ve always wondered about criminal lawyers, Bert?’ he said. ‘How anyone can stand up in court and defend a person they think is guilty?’

‘Good question,’ Brechin said, ‘but one I think better directed at Mr Munro. Defending the guilty is something he’s made a career of.’

Laughing, Ted turned to me. ‘Is that right, Robbie? How can you do it?’

‘I do it because some of those people are actually innocent, and someone has to stand up for the wrongly accused.’

Ted swirled the last of the red wine in his glass and threw it back. ‘Sounds like one of those dirty jobs that someone’s got to do. Joanna tells me you’ve had a few famous victories in your time.’

It was meant as a compliment, and I would have accepted it and left things at that, but for the sarcastic snort from across the table. I’d heard that snort so often in court that I didn’t have to turn my head to establish the origin.

‘Not so many victories as I’d have liked,’ I said, aware of the steely grip Joanna had taken on my thigh. ‘Or should have had. You see, while it’s my job to defend the wrongly accused, it’s the job of others to judge them. Unfortunately . . .’ I continued, ignoring the introduction of Joanna’s nails into the gripping process, ‘some of those whose job it is to judge guilt and innocence, wouldn’t know an innocent person if they stood right in front of them.’ I turned my head to look Brechin straight in his oyster eyes, adding for clarification, though by his beetroot face none was required, ‘In the dock of the Sheriff Court.’

When the Sheriff spoke, his lips scarcely moved. ‘If you are insinuating that I am an unfair judge—’

‘I’m not insinuating anything,’ I said. ‘I’m stating that there are too many people who think that the definition of justice is a finding of guilt, and yet the last time I looked, Lady Justice had two pans in her set of scales.’

‘Leave it, Robbie,’ Joanna said, placing a hand over the top of the wine glass that her uncle was determined to refill.

Brechin agreed. ‘Yes, Mr Munro. Don’t say something you may later regret.’

The others at our table had stopped chatting and were leaning in, lapping it up, and, by the expression on his face, Uncle Ted was beginning to think that maybe the price of my ticket had been worth it after all.

‘Come now, Joanna, Bert, let the man speak,’ he said. ‘We’re all friends here. I’m sure no-one is going to take offence at a little after-dinner legal debate.’

I didn’t need any encouragement. ‘Antonia, how old are you?’

Confused, the young woman looked at her grandfather and then back at me. ‘Twenty-three.’

‘And with your whole career ahead of you. Did you know that earlier today your grandfather convicted a woman, not much younger than you, of assault, all because she’d slapped her boyfriend on the face during a row? A young woman whose career in teaching is now over before it’s even had a chance to begin.’

It was unfair of me to bring Antonia into it. I knew that as soon as I had spoken the words. She blushed with embarrassment and played with the gold chain around her neck.

‘That’s quite enough,’ Brechin snarled across the table at me. ‘It is no good repeating your argument from earlier today. I had to listen to it for quite long enough as it was. Your client committed an assault, plain and simple. I am very sorry if the law of Scotland doesn’t meet with your warped sense of justice. Unfortunately, it is the job of some of us to apply it, not twist it to suit our own ends.’

‘No matter if the consequences far outweigh the offence? That’s not justice.’

‘Perhaps not. But it is the law.’

‘No, it’s not,’ I said. ‘The law does not concern itself with trivialities. It’s only because the Lord Advocate’s zero tolerance policy dictates that every row between a man and woman must equate to domestic abuse that the case ever made it to court.’

Ted caught a passing waiter by the sleeve. ‘What if it had been the other way about?’ he asked, after ordering up another round of drinks, rehearsing the line put to me by Brechin in court. ‘What if this girl’s boyfriend had slapped her?’

‘That would be different,’ I said.

Ted pointed his finger. ‘Aha, got you there, Robbie. Equal rights. What’s sauce for the goose . . .’

‘Not when the gander is six foot two and built like a brick chicken house and the goose is five foot one and eight stones soaking wet,’ I said. ‘If she’d shot him or stabbed him, fair enough, but a slap? Come on.’

‘An assault is an assault.’ Brechin was intent on having the last word. Nothing unusual there. ‘My verdict might have seemed like an injustice to you and your client, Mr Munro, but I’d sooner resign my position than bend the law. To quote Oliver Wendell Holmes Junior, I preside over a court of law and not a court of justice.’

Trust Sheriff Brechin to take literally a tongue-in-cheek obiter remark, just so long as in his twisted mind it justified a conviction.

‘Very good, Bert. Very good,’ Ted said, enjoying every minute of it. ‘What do you think about it all, Joanna? You’re probably best placed to give a balanced view, having worked both sides, prosecution and defence.’

Joanna smiled diplomatically. ‘Just like you say, Ted. I can see both sides of the argument.’

‘Come on, Jo-Jo, don’t be shy,’ Ted said. ‘We’re all lawyers here. Pick a side and argue your case.’

The waiter arrived with a tray, noticeably absent of further refreshments. He whispered something to Ted, and the inclination of his head was followed by everyone at the table to a clot of blue uniforms standing on the other side of the ballroom.

Brechin couldn’t resist. ‘Looks like there may be some business for you, Mr Munro. Nothing too de minimis, I hope.’

He smiled at Ted. Ted didn’t smile back. Two evening dresses stood up at nearby tables. Slowly they began to float across the room to the awaiting police officers.

As I was trying to think up some caustic remark to throw back at Brechin, I couldn’t fail to notice that the colour had drained from his granddaughter’s previously flushed face.

That and the fact that she too was rising slowly to her feet.

5

I hadn’t known Ellen Fletcher in her younger days. I’d first acted for her only a year or so before, when she’d lost her husband, fallen on hard times and embarked on a career as an inept shoplifter-slash-credit-card-fraudster. Though she’d often been caught, she’d had only the one small taste of prison, a week’s remand before a successful bail appeal. I’d been recommended to her by Jake Turpie, my former landlord, who’d k

nown Ellen forever. She came from Croy originally, a small town, third stop on the train line from Linlithgow to Glasgow. A town where a lot of people got on and even more people didn’t want to get off.

Apparently, Ellen had been a real looker back in the day. Ellen of Croy, the face that launched a thousand pub fights. But if her face had once been her fortune, these days it was accruing less interest. Or perhaps I was being unfair. Whenever I saw Ellen she was dressed down and in her working clothes. No make-up, no hair-do, just another woman doing the shopping. Someone not out to attract attention. Not while she was filling her tinfoil-lined carrier bag with anything from packs of razor blades to jars of coffee to designer labels. However, on this Friday afternoon Ellen was almost unrecognisable. Hair up high, the neckline of her evening gown down low, she looked more like the madam of a Texas cathouse than a recently retired shoplifter.

Ellen had taken a suite on the top floor of the Balmoral, and we sat in comfortable armchairs in the sitting room, chatting and polishing off what was left of the bottle of champagne she’d been drinking upon my arrival. When Ellen rang for room service it took three porters to deliver another, which had nothing to do with the logistics of the exercise and everything to do with her tendency to tip like a lorry at a landfill.

Ellen closed the door, put her purse back into a big pink handbag and handed me the bottle to pop. ‘I like it here,’ she said. It certainly had prison beaten hands down.

Good News, Bad News

Good News, Bad News